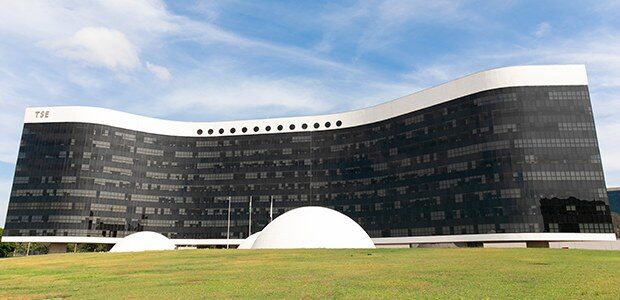

Image: The Superior Electoral Court (TSE) a branch of the Brazilian judiciary that oversees the country’s election processes.

by Iná Jost

Head of research in InternetLab. Lawyer graduated from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. She held a master’s degree in international relations and human rights at Sciences Po, in Paris, where she specialized in freedom of expression, journalism and Latin America.

General Context

On March 1, 2024, the Superior Electoral Court of Brazil published 12 resolutions that will govern the 2024 elections, aimed at electing mayors and council members of the country’s 5,568 municipalities for the term 2025-2028.

Brazilian electoral resolutions are norms issued for each electoral process and aim to regulate federal legislation on elections (Article 105 of the Electoral Law), adapting general norms to specific contexts. They address various topics, such as electoral polls and candidate registration. For example, they establish the calendar that will govern the year’s activities and update the values for the distribution of the Special Campaign Financing Fund. Considering that they are issued by a judicial body, these provisions should not bring legislative innovations. This text addresses some of the most relevant points of Resolution No. 23,732/2024, regarding electoral propaganda, which seeks to accommodate the rules governing political advertisement to the new realities of the digital environment.

A note on the process

Before delving into the merits of the norm itself, it is important to make a brief comment about the formalities of the drafting and approval process of TSE resolutions. This process is conducted by the Court’s vice presidency office and is always preceded by the publication of draft texts. These initial versions are subject to public hearings, during which TSE receives written and oral contributions from various sectors of society. After receiving the inputs, the vice presidency office edits the final texts and submits them for plenary voting. Once approved, the regulations are published and already apply to the next electoral process.

Specific aspects of the 2024 process

As tradition dictates, in 2024, TSE published draft texts of the resolutions and held public hearings to receive comments and suggestions from interested entities from all sectors. According to the Court itself, the sessions achieved record participation. Among civil society organizations, public sector bodies, and digital platform teams, the process received 80 oral contributions and 945 written ones.

However, when the final text was published, the entities that engaged in the process were surprised by a provision that was not included in the earlier versions. Amid other innovations, Article 9-E brought controversial changes in the intermediary liability regime during the electoral process. This and other changes are described below.

Key points of the new text on political advertisement

Change in the liability framework for intermediary platforms – Article 9-E

As mentioned, the most controversial provision of the resolution is article 9-E,that altered the intermediaries liability regime established by the Civil Rights Framework for the Internet (Marco Civil da Internet, MCI). The wording of MCI’s article 19 establishes that platforms would only be civilly liable for content published by third parties if they fail to comply with judicial removal order, under the logic of avoiding undue monitoring and suppression by providers. Furthermore, the Electoral Law itself, in its Article 57-F, repeats the terms of MCI, reproducing its liability model for electoral propaganda.

Article 9-E, however, introduces the possibility of civil and administrative liability for these companies when they fail to immediately remove five groups of content considered as “risk cases.” In summary, (i) antidemocratic conduct, (ii) disinformation dissemination, (iii) threat to the integrity of institutions and their members, (iv) hate speech, (v) failure to comply with the obligation to label artificial intelligence content, brought by the resolution itself.

The provision worried stakeholders in the discussion, mainly for two reasons:

- The first, the fact that it is an instruction issued by a Court that expressly contradicts federal laws, namely, the Electoral Law and the Civil Rights Framework for the Internet. The purpose of TSE’s resolutions is to regulate existing provisions, not to modify parameters established by the legislative branch. Two liability regimes for intermediaries cannot coexist in the Brazilian legal system.

- Additionally, regarding its practical application, the consequence of the resolution is precisely what the Civil Rights Framework seeks to avoid: private censorship by the platforms in question. Once they incur the risk of civil and administrative liability, companies may opt for the route of securing and preserving their own services and operations, at the expense of user’s freedom of expression, as well as the free circulation of speech. This is a perverse consequence of the resolution because it encourages providers to act as curators of public debate, particularly during electoral periods, when dissemination of content, be it news, political advertisement, opinions, or others, reaches the peak of its democratic value.

Other provisions of the resolution

In addition to the change in the liability regime, Resolution No. 23,732/2024 brought several provisions with new arrangements and obligations for candidates, parties, and platforms. Article 9-C, for example, expressly prohibits the dissemination of disinformation content, with the following wording: “notoriously untrue or decontextualized facts with the potential to cause harm to the balance or the integrity of the electoral process.” Article 9-C § 1, in turn,specifically prohibits the use of deep fakes, a concept defined as «synthetic content in audio, video, or combination of both formats, which has been digitally generated or manipulated, even with authorization, to create, replace, or alter the image or voice of a living, deceased, or fictional person.”

Article 9-D presents an explicit prohibition on sponsoring content containing disinformation on social networks. The provision is relevant because Brazilian legislation authorizes paid political advertising on digital platforms (Article 57-C of the Electoral Law) through the figure of “content boosting.” Additionally, the same article prescribes various obligations for platforms, such as the drafting of terms of use aimed at reducing the circulation of disinformation, the implementation of complaint channels, the publication of transparency reports disclosing actions taken to improve content recommendation systems, the performance of impact assessments of services on electoral integrity, among others .

The resolution also brings changes for the use of artificial intelligence (AI). Article 9-B regulates its employment in electoral campaigns by requiring explicit labeling when the tool is used. It specifies, for example, that audio and video pieces must come with prior notice of the technology application, and requires the use of watermarks and audio description in images and videos. The resolution also provides an exception for such labels in cases of AI aimed at improving image or sound quality, production of visual identity and brands, and commonly used advertising resources in campaigns, such as photo montages.

Finally, the regulation brings transparency advances by inaugurating a public ads repository, an updated library that compiles, in real-time, advertisements, their validity period, values, and characteristics of the targeted users. Until now, apart from campaign expense declarations, in which candidates declare their expenditures during the electoral period, there was no instrument revealing information about the reach and audiences of sponsored posts on social media.

Conclusion

The publication of Resolution No. 23,732/2024 has sparked wide-ranging debates among the various actors involved in platform regulation and its intersections with elections in Brazil. On one hand, it addresses longstanding concerns imposing transparency obligations on platforms, such as the creation of ads repositories, where voters can track the amounts spent on advertising by candidates and parties. Additionally, it introduces a first regulatory approach to artificial intelligence, with reasonable provisions regarding, for example, the need to label content that uses the tool.

On the other hand, it introduces a rule into the legal framework that has the potential to infringe upon the right to freedom of expression on the internet, generating more doubts than legal certainty. Additionally, it crosses dangerous lines of competence of a judicial body to introduce legislative innovations that contradict federal principles. Despite the enormous challenge of combating misinformation, it cannot allow for the relaxation of federal processes and laws.

It’s worth noting, moreover, that since 2020, Brazil has been in a continuous process of discussing a bill (2630 PL / 2020) aimed at updating the regulation of the digital environment, bringing various transparency obligations and systemic actions to promote safe, plural, and diverse spaces for expression. However respectful the intentions of TSE may be, and however enduring and complex the legislative process is, it is within this branch that the capacities and authorities reside to issue regulations of this nature, and it is from there that a robust, legitimate, and effective framework should emerge to address the challenges presented by the digital ecosystem.