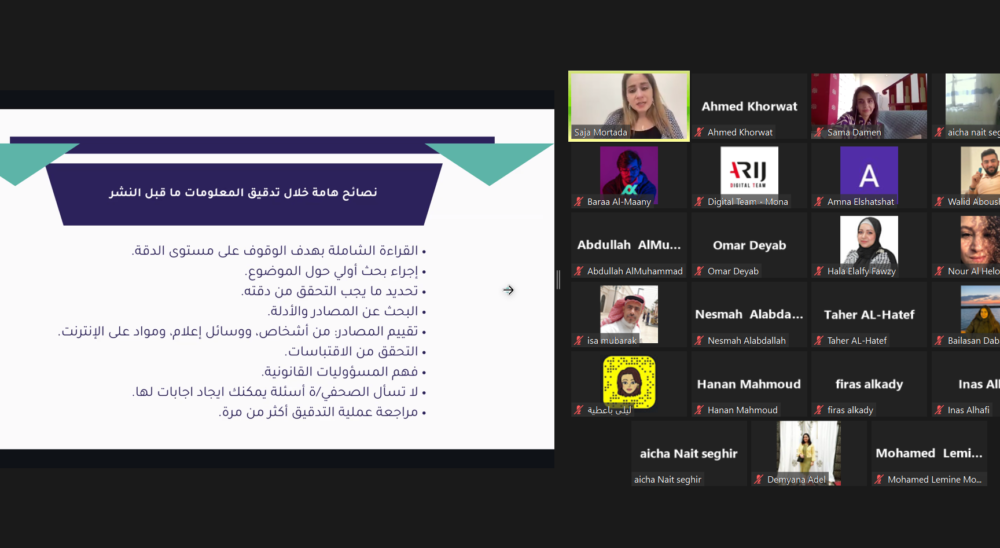

Image: ARIJ’s AFCN Workshop: Fact-Checking Basics – Methodologies and Tools. 27 May 2024.

by ARIJ’s AFCN team.

The definition of fact-checking is the process of verifying information to ensure it comes from reliable sources. This process is applied to all journalistic content, including elements such as photos, texts, videos, and other multimedia.

There are two types of verification. The first one is pre-publication fact-checking, designed to build and maintain the credibility of media outlets. The second is post-publication fact-checking, which focuses on the factual accuracy of content published in traditional media outlets, and on social media platforms, as well as reviewing statements issued by politicians and officials.

Post-publication fact-checking aims to detect and correct any mis/disinformation. Both pre- and post-publication fact-checking work hand in hand to combat the spiralling information disorder.

Pre-publication fact-checking dates back to the 1920s, when the US Time magazine initiated this practice, only to be followed by other media outlets. Despite facing a backlash, pre-publication fact-checking has not been consistently applied to all pieces of writing. The American newspaper The New York Times’ “Guidelines on Our Integrity” (issued in 1998) states:

“Fact Checking. The writers at The Times are their own principal fact-checkers and often their only ones. (Magazine articles, especially those by non-members of our staff, are fact-checked, but even magazine writers are accountable in the first instance for their own accuracy.) Concrete facts such as distances, addresses, phone numbers, and people titles must be verified by the writer with standard references like telephone books, city or legislative directories, and official Web sites.”

As a result of the revolution witnessed in recent years in the communication technology sector, as well as artificial intelligence (AI), the need for pre-publication fact-checking has become increasingly important. This has become especially necessary due to instances of fabrication exposed in prestigious media outlets.

The most famous example was the scandalous act of a Der Spiegel reporter, who fabricated content about the war in Syria and Iraq in 2018. The USA Today newspaper fell victim to a similar case in 2022.

As a result, key international media outlets such as The New York Times, and The New Yorker have been working to hire teams of fact-checkers, either as freelancers or full-timers, to avoid undermining the audience’s confidence in their content.

The process of verifying content to ensure accuracy follows specific methodologies that rely on verifying the authenticity of sensitive content as well as following the three staged verification like the process used in investigative reporting to verify all information.

Such model was adopted by the investigative programs at Sverige’s Television, which is Sweden’s national broadcaster (SVT), using the “three checkpoints” methodology, starting with fact-checking from the beginning of an investigative story through to the editor’s review, and ending with a check for factual accuracy.

In the Arab world, few media outlets have adopted systematic pre-publication fact-checking based on a study conducted by the Arab Fact-Checkers Network (AFCN), led by Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ). Pre-publication fact-checking has recently been adopted in some Arab countries with Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ), incorporating it into its editorial cycle from 2019, where a fact-checker is usually assigned to review the factual accuracy of any story before its publication.

ARIJ’s method varies from methodologies adopted in Alqatiba, a Tunisian media outlet, which assigns this task to a member of its editorial team. To date, none of the mainstream Arabic media outlets have taken the step to create their own fact-checking department.

Another common factor among many Arab media outlets like Sowt Podcast, and Alqatiba for example, is that they do not adhere to any methodology in implementing pre-publication fact-checking, leaving the verification procedure to be carried out at the editor’s discretion and expertise.

In almost all Arab media outlets, the editors or their fact-checkers, have never received any pre-publication fact-checking training before being assigned to undertake such crucial work.

In September 2023, ARIJ’s AFCN, in collaboration with Free Press Unlimited (FPU), selected 3 media organisations from the MENA region, to provide them with the services of a dedicated fact checker. Those outlets were Daraj from Lebanon, SIRAJ from Syria, and Almasry Alyoum from Egypt.

For a six-month period, the nominated fact checker worked closely on putting in place a fact-checking methodology to fact-check some of the content produced before publication.

The project aimed to integrate the pre-publication fact-checking process within the editorial workflow of the three chosen independent media outlets in the Arab world. As a result, all three entities have their own dedicated pre-publication fact-checking methodology, and all three have come to realise the importance of having an independent fact-checker within their team.

In 2024, AFCN’s researchers have realised that most Arab media organisations have so far misunderstood the concept of pre-publication fact-checking, and most often, they tended to think wrongly, that it was another editorial step like proofreading, or is simply to verify the existence of supporting evidence and resources, while most of them don’t have an independent fact-checker within their team.

As a result, Arabic media outlets face many challenges and obstacles in fully applying systematic pre-publication fact-checking. This is due essentially to their limited financial resources that are often insufficient to assign fact-checkers to review all write-ups, and to the outlet’s inclination of prioritising publishing material speedily over verifying the news content.

In the second survey of the IDRC study that AFCN’s team prepared, most Arab outlets have admitted that they lacked pre- publication fact-checking know-how, and most needed help to build capacity in this domain. This is in addition of course to the lack of implementation of the access to information laws in Arab countries which poses a fundamental obstacle for journalists and fact-checkers to access official reliable information.

In conclusion, although the pre-publication fact-checking has begun to be adopted even in baby steps in media organisations in recent years to deal with the larger waves of disinformation eroding the confidence in the media landscape, Arab media outlets still face challenges in applying a clear methodology for pre-publication fact-checking, for several economic, professional and political reasons.